New South Wales in Australia recently passed an anti-graffiti law that could see juvenile offenders jailed for up to 12 months. New York state has made it illegal to sell spray paint to anyone under 18, and Singapore has even physically canned graffiti artists as punishment. But when it comes to the Israeli occupied and blockaded Gaza Strip, local government not only tolerates graffiti, but actually provides workshops on how artists can improve their technique.

Part propaganda, part art

New South Wales in Australia recently passed an anti-graffiti law that could see juvenile offenders jailed for up to 12 months. New York state has made it illegal to sell spray paint to anyone under 18, and Singapore has even physically canned graffiti artists as punishment. But when it comes to the Israeli occupied and blockaded Gaza Strip, local government not only tolerates graffiti, but actually provides workshops on how artists can improve their technique.

Part propaganda, part art

Hamas facilitates the work of its graffiti artists - even purchasing spray paint for them.

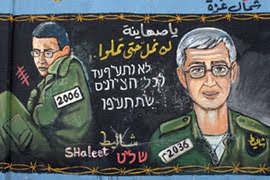

The Islamic Resistance Movement, Hamas, which has controlled Gaza since 2007, fully facilitates the work of its graffiti artists - from purchasing spray paint, to inviting artists to work on choice locations. Elaborate, colourful calligraphy brightens the drab streets and alleys of the Gaza Strip's densely populated towns and refugee camps. Most is political in nature, inscribing slogans of defiance against the Israeli occupation, or commemorating fallen martyrs. Some is apolitical, congratulating newly weds on their marriage, or pilgrims who have completed the Muslim obligation of Hajj.

Graffiti in Gaza is by no means the sole domain of Hamas. All political factions control crews of artists to prop up their influence and credibility. Part propaganda, part free-standing works of art, Gaza's graffiti is deeply ingrained in the local society's historical and political fabric. "During the first Intifada we had no internet or newspapers that were free of control from the Israeli occupation," explains Ayman Muslih, a 36-year-old Gaza graffiti artist from the Fatah party who started painting when he was 14 years old.

"Graffiti was a means for the leadership of the Intifada to communicate with the people, announcing strike days, the conducting of a military operation, or the falling of a martyr."

The graffiti Muslih and others put up on Gaza's walls was strictly controlled by each political party and their respective communications wings. Select individuals were delegated to hide their identities by covering their faces with scarves and to brave the Israeli military-patrolled streets to put up specific slogans.

"Writing on the walls was dangerous," recalls Muslih. "I had good friends who were killed by Israeli soldiers who caught them." Spray paint colours became associated with each political group, with green preferred by Hamas, black by Fatah, and red for leftist groups.

The competition for popular support and leadership of the first Intifada was visually expressed in the amount of real estate each political party's graffiti was able to capture. First Intifada graffiti never developed too much artistically however because by nature it needed to be produced in as short a period of time as possible, to avoid detection.

Hamas facilitates the work of its graffiti artists - even purchasing spray paint for them.

The Islamic Resistance Movement, Hamas, which has controlled Gaza since 2007, fully facilitates the work of its graffiti artists - from purchasing spray paint, to inviting artists to work on choice locations. Elaborate, colourful calligraphy brightens the drab streets and alleys of the Gaza Strip's densely populated towns and refugee camps. Most is political in nature, inscribing slogans of defiance against the Israeli occupation, or commemorating fallen martyrs. Some is apolitical, congratulating newly weds on their marriage, or pilgrims who have completed the Muslim obligation of Hajj.

Graffiti in Gaza is by no means the sole domain of Hamas. All political factions control crews of artists to prop up their influence and credibility. Part propaganda, part free-standing works of art, Gaza's graffiti is deeply ingrained in the local society's historical and political fabric. "During the first Intifada we had no internet or newspapers that were free of control from the Israeli occupation," explains Ayman Muslih, a 36-year-old Gaza graffiti artist from the Fatah party who started painting when he was 14 years old.

"Graffiti was a means for the leadership of the Intifada to communicate with the people, announcing strike days, the conducting of a military operation, or the falling of a martyr."

The graffiti Muslih and others put up on Gaza's walls was strictly controlled by each political party and their respective communications wings. Select individuals were delegated to hide their identities by covering their faces with scarves and to brave the Israeli military-patrolled streets to put up specific slogans.

"Writing on the walls was dangerous," recalls Muslih. "I had good friends who were killed by Israeli soldiers who caught them." Spray paint colours became associated with each political group, with green preferred by Hamas, black by Fatah, and red for leftist groups.

The competition for popular support and leadership of the first Intifada was visually expressed in the amount of real estate each political party's graffiti was able to capture. First Intifada graffiti never developed too much artistically however because by nature it needed to be produced in as short a period of time as possible, to avoid detection.

Public gallery

The graffiti of the second Intifada developed more artistically than that of the first

After the Palestinian Authority (PA) established itself in Gaza in 1994, more traditional means of communication with the local population took root, including national newspapers, radio and television stations and mobile phones. While the more relaxed political atmosphere during the peace process was indeed more conducive to the retreat of political graffiti, the phenomenon never fully disappeared, perhaps because its function could not be so easily replaced by the traditional means and boundaries of political commentary.

The PA's arrival also created the conditions for graffiti to evolve qualitatively. The Israeli army's re-deployment outside most of the main Palestinian towns and refugee camps gave artists the time and space to better prepare and deliver their work. Thanks to a $5mn Japanese donation to the PA to white wash miles of Gaza's graffiti strewn roadways, a graffiti artist's perfect canvas and public gallery emerged. With the eruption of the second Intifada in 2000, Gaza's graffiti culture re-emerged in full force.

Arsenal of tools

The factional competition between Fatah and Hamas and the steady flow of Palestinians killed by the Israeli occupation, created limitless material for graffiti artists who experimented with large murals commemorating the dead, or much smaller, but reproducible stencils.

Hamas particularly sought to take the discipline of graffiti art to new levels, seeing it as a part of the organisation's arsenal of tools to propagate its world view, including promoting a resistance agenda against Israel (as opposed to the negotiations approach of the PA), and propagating the Islamisation of Palestinian society. Hamas began offering courses for graffiti artists that trained them in the six main Arabic calligraphic scripts, known as al Aqlam aSitta: Kufi, Diwan, Thulth, Naksh, Ruq'a and Farsi. Delivery of high-quality calligraphy graffiti was part of the religious movements' more general reverence for the Arabic language, the sacred language of the Quran.

Tagging for the party

Public gallery

The graffiti of the second Intifada developed more artistically than that of the first

After the Palestinian Authority (PA) established itself in Gaza in 1994, more traditional means of communication with the local population took root, including national newspapers, radio and television stations and mobile phones. While the more relaxed political atmosphere during the peace process was indeed more conducive to the retreat of political graffiti, the phenomenon never fully disappeared, perhaps because its function could not be so easily replaced by the traditional means and boundaries of political commentary.

The PA's arrival also created the conditions for graffiti to evolve qualitatively. The Israeli army's re-deployment outside most of the main Palestinian towns and refugee camps gave artists the time and space to better prepare and deliver their work. Thanks to a $5mn Japanese donation to the PA to white wash miles of Gaza's graffiti strewn roadways, a graffiti artist's perfect canvas and public gallery emerged. With the eruption of the second Intifada in 2000, Gaza's graffiti culture re-emerged in full force.

Arsenal of tools

The factional competition between Fatah and Hamas and the steady flow of Palestinians killed by the Israeli occupation, created limitless material for graffiti artists who experimented with large murals commemorating the dead, or much smaller, but reproducible stencils.

Hamas particularly sought to take the discipline of graffiti art to new levels, seeing it as a part of the organisation's arsenal of tools to propagate its world view, including promoting a resistance agenda against Israel (as opposed to the negotiations approach of the PA), and propagating the Islamisation of Palestinian society. Hamas began offering courses for graffiti artists that trained them in the six main Arabic calligraphic scripts, known as al Aqlam aSitta: Kufi, Diwan, Thulth, Naksh, Ruq'a and Farsi. Delivery of high-quality calligraphy graffiti was part of the religious movements' more general reverence for the Arabic language, the sacred language of the Quran.

Tagging for the party Gaza's graffiti culture has just been documented in a new book by Swedish radio and photo-journalist Mia Grondhal, who has been visiting and reporting on the region for more than 30 years.

Although never previously the focus of her news reporting, Grondahl began paying closer attention to Gaza's graffiti during the second Intifada when she became increasingly impressed with its evolving quality.

"It was some of the best graffiti I've seen, especially the calligraphy," notes Grondahl. "This is mainly the work of Hamas who are very careful about how they write the Arabic language. Fatah artists do not feel the same because they are a secular party, and to them it's not so important how you write, but what you write." For Grondahl, Gaza's graffiti tells a story that goes beyond the typical catchphrases that tend to be repeated about the Strip and its people.

"Gaza's graffiti is so integrated into the society which makes it very interesting. You're not out there tagging just for yourself. You are tagging for the party you belong to, the block you belong to, for a friend who is getting married, or a friend who was killed. It's an expression of the whole range covering life to death."

All photographs by Mia Grondahl.Mia Grondahl is a Swedish radio and photo-journalist based in Cairo. She is the author of Gaza Graffiti: Messages of Love and Politics (University of Cairo Press, 2009).

Toufic Haddad is a Palestinian-American journalist based in Jerusalem, and the author of Between the Lines: Israel the Palestinians and the US 'War on Terror' (Haymarket Books, 2007).

Source: Al Jazeera

Gaza's graffiti culture has just been documented in a new book by Swedish radio and photo-journalist Mia Grondhal, who has been visiting and reporting on the region for more than 30 years.

Although never previously the focus of her news reporting, Grondahl began paying closer attention to Gaza's graffiti during the second Intifada when she became increasingly impressed with its evolving quality.

"It was some of the best graffiti I've seen, especially the calligraphy," notes Grondahl. "This is mainly the work of Hamas who are very careful about how they write the Arabic language. Fatah artists do not feel the same because they are a secular party, and to them it's not so important how you write, but what you write." For Grondahl, Gaza's graffiti tells a story that goes beyond the typical catchphrases that tend to be repeated about the Strip and its people.

"Gaza's graffiti is so integrated into the society which makes it very interesting. You're not out there tagging just for yourself. You are tagging for the party you belong to, the block you belong to, for a friend who is getting married, or a friend who was killed. It's an expression of the whole range covering life to death."

All photographs by Mia Grondahl.Mia Grondahl is a Swedish radio and photo-journalist based in Cairo. She is the author of Gaza Graffiti: Messages of Love and Politics (University of Cairo Press, 2009).

Toufic Haddad is a Palestinian-American journalist based in Jerusalem, and the author of Between the Lines: Israel the Palestinians and the US 'War on Terror' (Haymarket Books, 2007).

Source: Al Jazeera