COMMUNITY RADIO & THE INTERNET:

A PROMISING UNION

by Lynda Attias and Johan Deflander

Since our radio has been connected to the Internet, our telephone bills are four times higher, but I've also seen that we communicate four times less with our community. - Zane Ibrahim, Bush Radio; Cape Town, South Africa

Africa's community radio stations play an active role in the process of local development. They inform the population, help people share experiences and knowledge, and facilitate exchanges. These stations are often integrated into the community and are accessible to members from all social strata, including the illiterate and speakers of non-written languages. Radio stations must cope with many difficulties, however, because they lack documentation and are usually located in isolated rural areas. The use of new information and communication technologies (ICTs) can potentially enable them to face some of the challenges. Given that radio is already well-established, plays an important role in the community, and encourages participation, we believe that, connecting it with the Internet, a highly interactive and information-rich medium, offers many prospects for local development.

Nevertheless, simply praising the virtues of a linkage between community radio and the Internet does not take us very far. There is a need to examine the perceptions, expectations, and needs of the community radio stations and the practical obstacles that this linkage entails. One of the major risks involved with introducing the Internet into community radio is that it may remain foreign to those it is intended for and therefore be useless. The process of applying the new medium is a delicate one, and this means that consideration must be given to whether or not radio broadcasters are able to use it in their daily work and whether they are prepared to invest in it.

COMMUNITY RADIO AND THE PANOS INSTITUTE OF WEST AFRICA

In the early 1990s, pressure exerted on West African national authorities by many players in civil society, including non-governmental as well as governmental organizations, produced a liberalization of most countries' airwaves and, as a result, a new kind of media - associative community radio - appeared in several countries. New radio stations, owned and managed by their communities were then able to go on the air - usually in difficult financial situations, but with levels of development and conditions that vary significantly from one West African country to the next. They have been broadcasting in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Benin for the last ten years, whereas in Niger, Guinea-Bissau, and Senegal they have come into existence only in the last two years. Because these radios are young and lack professional training, they all face significant organizational problems. Senegal has a total of only eight stations, but Mali has 106 private radio stations of many different varieties.

The Panos Institute of West Africa (PIWA) has been involved throughout the process, supporting civil society efforts to change broadcast regimes, providing training and technical assistance to the radio stations and producing and distributing programmes.

As part of its work supporting the new radio stations, PIWA has undertaken a variety of initiatives to promote the understanding and use of the Internet by community radio stations. One of these is BDP on line, an Internet-based alternative to shipping CDs or cassettes by mail, a service that is both slow and expensive in West Africa. Using BDP on line, twelve participating radio stations in ten French-speaking African countries[44] are able to use the Internet to upload or download programmes free-of-charge. The service serves twelve radio stations[45] in ten French-speaking African countries.

Internet training for West African community radio broadcasters has been another of PIWA's activities. Since 1998 a number of courses on Internet for radio broadcasters have been offered. Among these was a series of courses conducted to support the launch of a network linking radio stations in certain regions of Mali[46] and another series that began in the summer of 2001 for seven Senegalese community radio stations.[47]

This chapter weaves together comments from participants at the Internet workshops in Mali and Senegal and the authors' observations of the workshops and other PIWA activities conducted since 1998. It presents a picture of community broadcasters' perceptions of the Internet, including its importance for development, its usefulness in their journalistic work, and problems associated with the introduction of the new medium. The chapter concludes that a new approach is needed if the Internet is to be of use to Africa's rural radio stations.

THE INTERNET: A NEW DEVELOPMENT INDICATOR

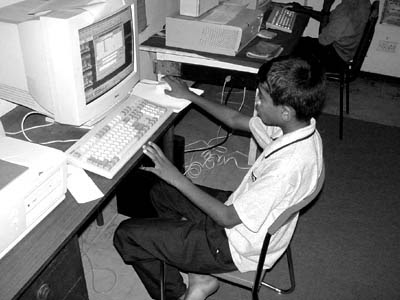

In Europe and North America computers have become an everyday household appliance, with most people having both access to them and knowledge of how to use them. However, African levels of computer use, especially in rural areas, bear no resemblance whatsoever to those of industrialized countries. During the Internet training workshops in Senegal and Mali, several broadcasters felt their hands shake as they grasped a mouse for the first time.

If you're not familiar with the machine, and you sit down with a computer expert, you think that you have a genius sitting next to you. I thought that I needed to have a superior intellect to be able to use it. (Radio La Côtière; Joal, Senegal)

Computers are considered to be complicated, inaccessible, and frightening tools associated with researchers and “superiour intellects”. The ability to use a computer is seen as a guarantee of learnedness. The technology, nevertheless, does not lack supporters.

With the evolution of new ICTs (new information and communications technology), it won't be long before you'll be considered illiterate or unschooled if you don't know how to use a computer. (Radio La Côtière; Joal, Senegal)

Rural and urban, men and women, young and old, all of the broadcasters said they urgently need to know how to use computers and the Internet for fear of becoming “the illiterate of the 21st century.” These words have a strong meaning in countries such as Senegal, Mali, and Burkina Faso, where more than 70 percent of the population is illiterate. That a failure to use new technologies could produce a new form of illiteracy represents a serious threat: the emergence of another cause for backwardness. It would seem that radio broadcasters now see the use of the Internet as a new development indicator.

We can't develop without this new Internet technology. We all have to understand that very clearly. We Africans are aware of it. (Radio Jiida FM; Bakel, Senegal)

New technologies are essential, and we have to go the way of the rest of the world.... We all talk about the global village, but we have to be part of that village. (Radio La Côtière; Joal, Senegal)

The Internet is a symbol of modernity. Not making use of it could mean not taking part in the global process, standing by as the gap between developed and developing nations widens, and being excluded from the highly touted global village.

FINDING INFORMATION ON THE INTERNET

The community broadcasters say that the Internet is useful primarily because of its informational potential. By being better informed themselves, they believe that they can more efficiently do their job of informing their communities.

What's most important about the Internet is that it enables us to broaden our knowledge and improve our programmes so that we can help our listeners. For example, there are many diseases that rural people don't know how to fight at the present time. The Internet can give us information on malaria, tell us what its effects are, which areas are the most affected, and how to prevent it. The Internet makes it possible for us to move toward information, to process it, and to provide people with it. (Radio Jiida FM; Bakel, Senegal)

Their Internet searches were directly related to local concerns such as agriculture, health, malaria, the rights of women and children, growing vegetables, fishing, and composting. They wanted to obtain clear, concrete, and precise information on certain issues from in the form of instructional and educational presentations so that they in turn could put together programmes on specific topics. However, they often found theoretical presentations or the kind of content that they felt could not be directly transferred into their radio programmes.

As for content, well, maybe you can find some things with advanced searches, but you don't usually come up with what you need. For example, while we were browsing with AltaVista I wanted something on turtles, but all I could find were pictures. In my opinion, that was just a waste of time and money. (Radio La Côtière; Joal, Senegal)

During the workshops the broadcasters usually included “in Senegal” or “in Africa” in their searches. For example, they typed “human rights in Senegal” or “agriculture in Africa.” They spontaneously wanted to assess how well their nation or culture was represented. The results were usually foreign content, even when the topics directly concerned them.

It hurts when you browse the Internet and the only information you can find on Africa comes from the USA or Europe. It simply means that Africa is very poor in terms of information. (Radio Jiida FM; Bakel, Senegal)

On the subject of Africa, from the time of my first search it seems that I've only seen reports. This tells me that foreign intellectuals are the ones who are reporting on us. What I would like to see is an African village presenting its own cultural life and history. I haven't seen any of that so far. I don't know if it exists or not, but, the way I see things, it should. (Radio La Côtière; Joal, Senegal)

West African radio broadcasters would like to feel that they can identify with the content of the Internet. However, the scarcity of sites allowing for them to do so makes them believe that Internet information on Africa is mainly a story about them, whereas what they want are not sites that talk about them but rather sites created by people like them.

INFLUENCE OR PROVOCATION?

Considering the disproportionate amount of Western information on the Internet, as compared to African information, the radio hosts wondered what kind of consequences the flood of Western content might have on Africa.

I think that the Internet is a melting pot where people can do and show whatever they want. In my opinion, here in Africa we have to protect our culture. Too much information from foreign sources could put our culture in jeopardy and change the thinking of young people and intellectuals. They could start to think that if the Canadians or Europeans do certain things, then we're entitled to do the same. All these things coming in from the outside are not good for us. (Radio La Côtière; Joal, Senegal)

I've been told that you can find some real scenes. That's no good for my conscience or for anyone else's. We can't allow that kind of thing. You open up the Internet, and you see a nude woman or words that don't go very well with our moral standards in Senegal. (Radio Oxy-Jeunes; Pikine, Senegal)

Pornography, on-line “encounters”, and information on subjects such as delinquency or prostitution can be contrary to customs and moral standards. Furthermore, some of the broadcasters mentioned that such information could be perceived as a provocation from dominant economies and as a risk to social stability. Therefore, it can be said that the Internet is seen as a showcase for the Western world in a context of underdevelopment.

I think there can be risks because we can come upon sites that are incompatible with our own way of life. We can be influenced because we're living in Africa in underdeveloped countries. Therefore we experience things in situations that are always difficult. We may aspire to live like Europeans even when we don't have the means to do so. (Radio Oxy-Jeunes; Pikine, Senegal)

Broadcasters are having a difficult time trying to position themselves somewhere between their fear of being backward and their will to affirm their own culture. Opening up to the rest of the world is a necessity, but protecting themselves is a priority. The Internet has only recently arrived in Africa, and community broadcasters are still only receiving information, using it as a one-way medium. There is still none of the kind of participation that will enable them to actively participate as information providers. However, many of the broadcasters in the workshops expressed their desire to see Africa and its radio stations develop their own sites.

Africans have to understand that it is a very useful tool and that they need to put information into it. We need to have lots of sites talking about development and about subjects relevant to Africa. (Radio Niani FM; Senegal)

Why not have Internet sites and also broadcast information on the radio? We can create sites just like anyone else can. There is some information that only we can provide. Why shouldn't we use it just like other people from other societies do on their sites? (Radio La Côtière; Joal, Senegal)

The broadcasters believed that the only way for them to make Internet content more relevant is to become involved in the Internet. This desire to participate opens the door to having the Internet serve radio. Even though most broadcasters do not yet have the technical skills required, it is relatively easy to learn and the Web offer a real possibility for exchange.

CREATING NETWORKS

During the workshops, broadcasters said they would like to use the Internet's interactiveness in two ways:

We'll be using the Internet mostly for the purpose of sharing information with other radios. It's important that we share programming with other rural radio stations. I want to be able to pick up other stations and find out what kind of content they have and what's going on with one radio or another. I want to gather information if I think that it's useful for my own village or locality. I think that it's important to have a network of rural radio stations. (Niani FM)

The Internet will make it possible for them to find out how other stations operate and design their programming. It will also encourage mutual aid among stations for the purpose of improving practices and helping to avoid isolation in different regions of the country. The Internet can also help radio hosts to find new funders more easily.

The Internet is important on the public-relations level. It can allow us to link with other organizations that would like to act but don't know where they can do it or with those that want to invest in radio on the European level but don't know where they can be useful. (La Côtière)

Broadcasters identified two kinds of partnerships that they can establish via the Web: with other radios and associations involved in the same work as they are; and with possible funding organizations. These partnerships could help to enrich content and provide funding.

LOCAL AND GLOBAL MEDIA: COMPLEMENTARY OR CONTRADICTORY?

Rural radio broadcasters clearly understand how useful the Internet can be. Whatever its prospective use, the goal remains the same: to make their radio station better.

I don't think that using the Internet will prevent us from doing our local work. The Internet is an aid, and it can help me to develop themes in my own local area. It's not going to change our approach to rural radio; it's only going to complement it. (Niani FM)

With the Panos Institute's e-mail project we'll be receiving information every day from Bamako or Gao.[48] That's important because Timbuktu doesn't receive any newspapers during the rainy season. (Radio Lafia; Timbuktu, Mali)

The Internet is seen as an informational supplement and a tool for exchange, but their own communities and realities remain at the heart of the process.

The Internet is important, and it has some good stuff, but you can't spend all your time with it. You can't make a priority of things coming to us from outside because, if you do, you'll forget about your own reality. (Oxy-Jeunes; Pekine, Senegal)

The broadcasters feel that using Internet means falling into line with the rest of the world, but also that they have to ensure that the flow of foreign information does not distance them from their communities. The Internet must be included in the station's mission and should not lead them astray from it. The objective is to support existing communication processes, not to replace them.

A DEMOCRATIC TOOL THAT IS NOT YET DEMOCRATIZED

The Internet is often called a “democratic tool” because it supposedly provides an opportunity for everyone to participate and because it is difficult to censor. However, if it is to be truly democratic, it must be accessible. At the moment there are many barriers that restrict radio stations' effective use of the Internet. These include financial barriers, organisational barriers, linguistic barriers and infrastructural ones.

Financial Barriers

After setting up the computer, we surfed for a few hours. A month later, we received a telephone bill for CFA200 000.[49] Our journalists didn't know that they had to disconnect after using the Internet. (Radio Hanna; Gao, Mali)

Financially speaking, community radios have a hard time surviving. They get along by charging small amounts for broadcasting dedications, death notices, community announcements, and personal messages. They are located primarily in rural areas where income-generating activities, including fishing and farming, do not provide people with enough to help their media to survive. Despite the potential of the Internet, the scarcity of money means that radio stations cannot use it.

The costs are even higher in the case of audio distribution projects like BDP on Line. It takes an average of one hour over an expensive telephone line to download a 15-minute programme. It is not very realistic to imagine that rural radios can exchange sound files or conduct regular searches on the Internet. Internet will become a tool that radios can use only if national and international access strategies are implemented. A priority for rural radio stations might be to lobby authorities for free or low-cost Internet access. This would certainly be a useful step toward a real democratization of the Internet.

Organizational Barriers

Even though a radio station may have a computer that can be connected to the Internet, there are significant access problems for the members of the radio team. One facet of the access problem in rural areas is clearly related to organizational deficiencies in the radio stations: the computer, a precious asset, is kept in an office, where only the director or president will have access to it. Management of community radios is often not community-style. Even when it is, there are good reasons for limiting access to the equipment.

The current problem is maintenance. There are no maintenance specialists in Bakel (a city located 750 km from Dakar). When a computer breaks down, we have to take it to Dakar. With the cost and all the risks along the way, that's a real problem. There may have been just a slight memory block, but, if we're not experts, we have to stop our work, and the computer is useless. We know that people here won't have the means to repair it. (Jiida FM; Senegal)

This kind of difficulty causes radio directors to limit computer access strictly to the most skilled radio hosts, the result being that most hosts will remain unacquainted with the Internet tool.

Linguistic Barriers

The kind of language used on the Internet poses a problem. Rural broadcasters often have a fairly low level of schooling, and, although French or English may be the official language of a country, most speak their regional languages better than the official one. At the same time, much of the useful information on the Internet is written in a complex academic language that is inaccessible to many people. Some broadcasters are so disconcerted by the kind of vocabulary that they give up using the Web.

Infrastructural Barriers

Although using modern software does not constitute a major difficulty, local infrastructure does. In theory, every Senegalese city has enough bandwidth for the use of all Internet services. (Other countries are still suffering along with the old analogue exchange systems.) However, service interruptions are frequent and sometimes very long. Even in Bamako, Mali's capital city, the coordinator of BDP on Line has sometimes gone for days without access to the Internet, shutting down the entire network. In rural areas, service can be even less reliable. The electricity grid is also susceptible to failure, with power being cut for hours or even days at a time.

Furthermore, although other equipment is at times needed, many radio stations have nothing more than the computer itself. Printers, for example, would be useful in limiting the amount of connection time, particularly in the case of distribution lists or long documents, but most stations do not have one and even paper is expensive.

The practical obstacles mentioned above all pose serious questions concerning how the Internet can be used in community radio.

WHAT ABOUT ANOTHER APPROACH?

At present, new communications and information technologies can probably not be of direct use to Africa's rural radio stations, at least not in the same way in which they are in more developed parts of the world. It is possible, however, to combine the most advanced technologies - Internet audio, for example - with more traditional broadcasting techniques such as “radio relay”. Audio files could be exchanged over the Internet between national “flagship” stations located in the capital (these could be community-radio associations) and then sent out by more conventional means (cassettes, CD Roms) to the member stations. Other Internet options, such as exchanging text instead of audio are more realistic for everyday radio use.

For this strategy to be feasible, however, the national flagship stations need financial resources to pay for connection and communication costs, and they themselves must belong to a network comprising several countries with the ability to produce sufficient quality programming. Such a flagship network would also need a regional hub capable of providing training, financial support for its equipment, and full-time distance (electronic) service for advice and assistance.

In addition, several “intermediary” organizations with strong local roots - such as the Panos Institute of West Africa - could help to link new technologies (the Web or satellites) with local radio stations by selecting and formatting information from the Web and by supporting the development of networks.

PAVING HIGHWAYS

Making the Internet serve the needs of West African community radio is a work in progress. There is still a long road ahead, and the time it takes to get there will depend on the road conditions. That is why we need to provide routes free of potholes and obstacles, highways that are paved, fast, and efficient.

44] Those radio stations are the following: Anfani (Niger), Femmes Solidarité (Côte d'Ivoire), Golfe FM (Benin), Kledu (Mali), Korail FM (Madagascar), Minurca (Central African Republic), Nostalgie (Togo), Oxy-Jeunes (Senegal), Pulsar (Burkina), Sud FM (Senegal), Tabalé (Mali), and Studio Ijambo (Burundi).

[45] Those radio stations are the following: Anfani (Niger), Femmes Solidarité (Côte d'Ivoire), Golfe FM (Benin), Kledu (Mali), Korail FM (Madagascar), Minurca (Central African Republic), Nostalgie (Togo), Oxy-Jeunes (Senegal), Pulsar (Burkina), Sud FM (Senegal), Tabalé (Mali), and Studio Ijambo (Burundi).

[46] Participating stations were from Timbuktu, Gao, Mopti, and Ségou.

[47] Awagna FM, Gaynaako FM, La Côtière, Jeeri FM, Jiida FM, Niani FM, Oxy-Jeunes, and Penc Mi.

[48] Bamako is Mali's capital and Gao is another city in Mali.

[49] 200 000 West African Economic Community francs equals approximately US$265, Mali's per capita annual income is US$230.